This is a transcript of the keynote I gave at PyCon CZ 2016. It’s a bit lengthy, but hopefully worth your attention. Alternatively there’s a video recording of the talk you can watch.

Hello! Ahoj! Salut!

There used to be a time when a tech-savvy, computer person was regarded as a reclusive night creature that lived in the basement and loathed going outside and talking to people. There are developers who prefer to work at night and don't feel very comfortable interacting with others. And that's alright. But the stereotype's been changing.

Similarly to how technology and some forms of programming have been creeping into the mainstream, the typical programmer has evolved into a social person, who likes going to conferences, meetups and hack days, give talks and generally enjoys the company of others.

We all know being a programmer isn't only about writing code, drawing diagrams and navigating documentation. It's also about planning, brainstorming, arguing design decisions with your team, giving and receiving feedback, joining client meetings and discussions, finding a middle-ground between clients' or communities' requirements and real world possibilities and being able to explain that.

Suppose our different sets of skills are a layered cake. Yum!

One big layer is dedicated to technical expertise...

... and another layer for social competence.

Truth is, we still prioritize technical expertise over social and emotional education. Just think about the plethora of books, tutorials and articles that teach us coding. Even the most niche little things, find a community of devs that care about it and want to share and learn.

Conversely the social aspect of what makes a good developer isn't referred to very often.

What does it actually mean to be a good developer from a social point of view?

Is it about smiling to each other all the time? Or is it about general courtesies like saying "Hi", "Bye" and "Thank you"? It's definitively about not insulting or harassing your team or community.

This talk isn't exactly going to be about that.

This talk is about the subtle "that wasn't quite right" moments and all sorts of invisible interactions that happen all the time between us and can inconspicuously shape the general mood around us. It's that slim layer of the cake.

This is our first story: "Beginners & Mentorship".

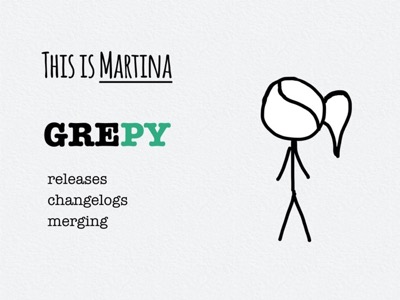

Meet Martina. Martina is the maintainer of open source project grepy. She handles the releases, changelogs and merging code into upstream.

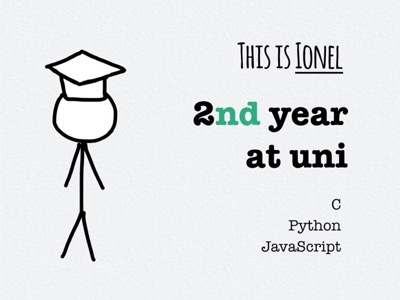

This is Ionel and he is currently in his 2nd year at university, has been using C for a while and knows a bit of Python and JavaScript. He really likes grepy and has been using it for a while. He figured he's missing an itty-bitty feature - making grepy search for case-insensitive patterns.

He knew that the tool is "open source". He heard that open source is like getting access to some code to which he can make a modification and then share with everybody and everyone will be very grateful to him.

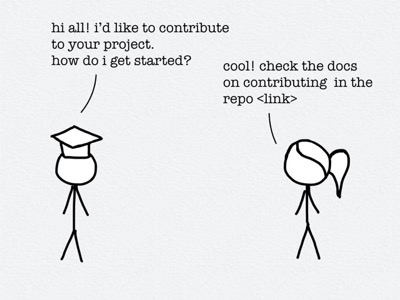

Ionel, all enthusiastic, firstly finds out what the IRC address of the grepy community is, joins and says: "Hi all! I'd like to contribute to your project. How do I get started?". Reply back: "Welcome :) To get started check the documentation on contributing in the repo."

Ionel cracks on with the code, spends about a week of free time in total to implement the feature and creates a pull request. In the comments he says "Hi. This is feature so and so and my first pull request ever. I'm a total beginner." Here comes the moment of truth!

Martina finally finds some spare time to review the code. She glances over the PR and leaves a couple of comments: "Please remove the loop and change this variable name. For the PR to be accepted we require unit tests and documentation. Back to you."

Ionel is crushed by this message. What the hell are unit tests? How do I add docs? What exactly should I write? In reality it took Ionel 3 days to figure out how to run the project and then another 3 to write those 6 lines of code. He can't understand why his code can't be merged as is. It works, right? Due to growing frustration, Ionel gives up and never makes the second PR.

In an alternate universe, this is what could have happened.

Martina glances over the PR and leaves a couple of comments: "Hi, thanks for your contribution. Good job on feature X. Please remove the loop and change the variable name. For the PR to be accepted we require unit tests and documentation. Back to you (smiley face)."

This is called sandwich feedback: say something nice, say something not so nice, and end with niceness again. It's somewhat better than the previous version, but it feels insincere, and people can feel that. We can do better.

In an alternate universe, take II.

"Hi, thanks for your contribution! We really appreciate having beginners on the project.

I see you are using a loop to make the string lowercase. That looks like a valid piece of Python code. You were probably not aware of that, Python has a built-in method for that called "lower". You can do 'aNyStRiNg'.lower() and it will convert the entire string to lowercase. Neat, right?

Don't worry about missing this, I still have trouble remembering all of those functions and methods from Python STL.

Thank you for adding this feature to the grepy. Usually when we write new features, we find it very useful to provide some short docs on them. If you look into the docs folder, there is a file called features. Can you please add a line mentioning the case-insensitive argument, that'll be very helpful.

Ohh, and we also usually write tests. There's a lot of stuff to know about tests. Start by reading this and that. Follow our guide on adding tests.

If you get stuck, just ping me on IRC and I'll try to help you!"

Huh, that was verbose. What changed? Everything!

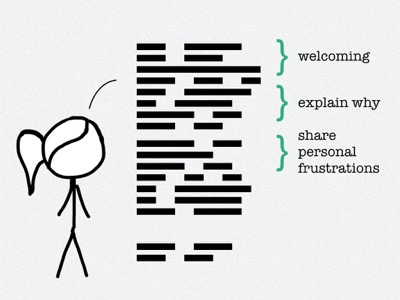

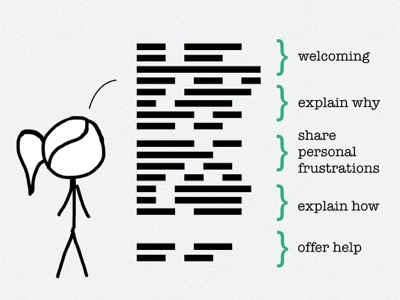

Let's break it down.

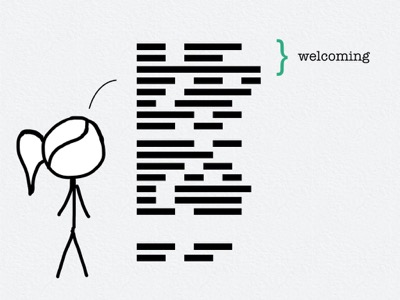

The intro: "Hi, thanks for your contribution! We really appreciate having beginners on the project."

Be welcoming. As beginners, they have taken a very big leap to make that first step. Give them some encouragement to keep moving. And if you consider that your project is not well-suited for beginners, more on that a bit later.

Only say that you appreciate having beginners contributing, if you really mean it.

Seriously, be honest. If you're gonna say things you don't believe, don't even bother. People can sense when you're talking from a template.

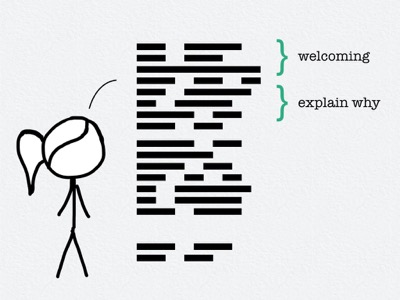

If you're asking for a change, take the time to explain why something is important. Just stating facts sounds like giving orders.

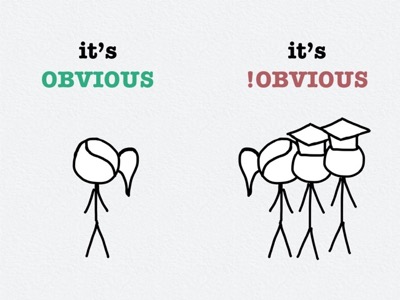

And you won't believe how some things obvious things to you aren't obvious at all for beginners or even other developers.

"Don't worry about missing this, I still have trouble remembering all of those functions and methods from Python STL."

With this you've established a very humane connection. You've admitted of your own flaws, which makes you seem more real and humane, not a super-creature (if you've actually memorized all of the Python STL, then don't lie for the sake of the contributor to feel good about themselves). You've connected with something very deep within yourself to understand what the person on the other side of the computer screen experiences.

This ability to put yourself in other people's shoes, to feel with them has a name.

It's called empathy.

Empathy is about taking perspective, withholding judgment, recognizing emotion in other people and communicating it. We all need a little bit more empathy, both on the giving and receiving end.

Along with explaining why, also explain how. If it's a simple task, make it sound simple. Don't obscure by using fancy words or shoveling in some elaborate concepts from computer science. It's just one line of text in a markdown file. And offer help, beginners need our help.

That was a lot, wasn't it?

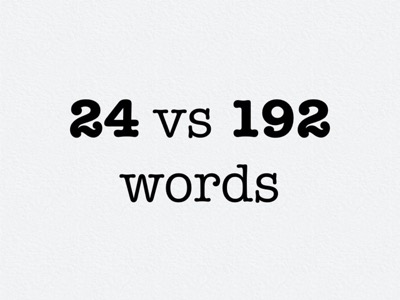

To be exact that's 168 more words than the first draft. But we know it's not about the quantity of sentences, right? It's about their quality.

To achieve this level of understanding and empathy, it takes a lot of energy. It takes enormous amounts of energy and emotional struggle for the beginner to make the PR and it's equally energy draining for the mentor to keep up. And when both sides can see each other's perspective, beautiful things happen.

I've set the focus on the mentor and their ability to be empathetic, because they have been beginners themselves and have a direct reference where to look, whereas beginners have rarely been mentors, hence lack that experience.

Don't forget to connect with your beginner self. Nobody is born knowing these things. We've all written bad smelly code and we kept on writing that bad smelly code, because nobody told us that we suck and we should never do that. Or maybe someone told you so, but you were stubborn, and brave, and continued regardless. But not everybody is. So don't discourage people. We grow professionally with time. Offer this time to beginners.

It's curious that almost every developer will tell you that when looking at their one year old code, they'll say "That is horrible, what was I thinking back then?". We accept our flaws, we know we are not perfect. Let's accept the fact that others aren't either and let them make mistakes.

Mentorship is not just about that. There's a whole lot more...

For me personally mentorship is an intersection of teaching, inspiring and guiding. It's hard work.

So open source...

I think beginners should have a safe playground to try things out without the pressure of perfectionism. Open source is often not the place, especially with a small, solitary, one maintainer, who probably also works full-time, projects. Lack of energy drives a lack of mentorship. Also consider most of us are not getting paid for it and even being shouted at by random people on the internet for not fixing a bug in time, because, you know, they need it.

What fascinates me is that there are projects that harvest the energy for mentorship. Often those will be big community, many contributors type of projects. These are the kind of projects that can afford to invest in good beginner documentation, that have people who can do so, who will often participate in Google CodeIn, Summer of Code camps and such. I want to say thank you :)

If you are a big community, but you prefer to neglect beginners, then you are losing some unique perspectives to improve your project and to self-evaluate.

Let's talk about legacy, also nicknamed "code archeology".

This is Lela. Lela has been working on this legacy project for the past 2 months. The more she got into it, the more she realized how big it is. It's been developed in the company for the past 3 years and before that it belonged to another agency, having in total about 50 contributors.

Lela has a bug to fix and first thing she does she writes a failing test and then git bisects until she finds the hurting commit.

Aaaaand the commit's author is herself. It looks like this is another fix that she did when she joined the project.

Going back in time when she first tried to fix whatever she was fixing, we can see how she acted. It was a side fix, she saw something that looked like an awkward way of accomplishing what she thought it was supposed to accomplish.

So she git blamed. Saw it was a person who already left the company, made a snarky comment to herself: "Ha, is that proper Python? Must be the reason someone got fired." So she changed a couple of lines of code as a matter of fact. As we know, it backfired.

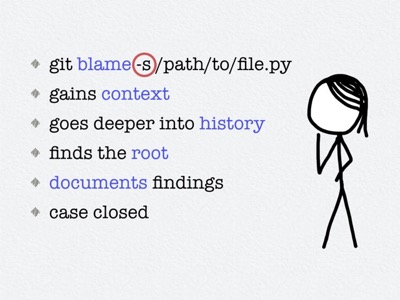

In an alternate universe, what could have happened?

Lela finds the odd looking piece of code, does git blame -s /path/to/file.py, because at this point it actually doesn't really matter who made the change. Finds the commit. Looks at the commit message and commit contents. She is gaining more context.

Seems like this bit of code was moved from somewhere else, so she does git blame before that commit - goes deeper into the history.

Finds out a very nice explanation on why it looks the way it looks and what it's supposed to serve. She found the root!

Lila leaves a comment in the code, summarizing everything she learned and why this shouldn't be removed. Case closed.

Git blame is an excellent tool if used for things beyond just blaming people.

Some people have strong feelings about the choice of words - blame.

We have an alternative. We can create an alias to git blame. Quoting from the original repo of this git praise alias: "Sometimes you find the most amazing piece of code and want to know who to thank for this wonderful contribution and then it feels wrong to use git blame."

But what if you personally rarely use git blame to literally blame someone or git praise to thank people (though that's definitely nice)?

Hence I came up with this alias - git travel. Because for me it's all about going back in time and like an archaeologist figure out why things are the way they are. It's not about me and my judgment, it's about the history. Most probably nobody is playing dump, there is a reason for this bit to exist.

Context makes a very big difference and that's why it's worth spending time to understand project history. All code is legacy or will be some sort of legacy soon enough (you don't need decades for that), otherwise we wouldn't have big and complicated systems. So knowing your way around legacy is a skill we should develop.

Couple of years ago, while at university, I stumbled upon this article that discussed a very complex codebase of a system. And it's presented from the perspective of the new architect that decides to makes a big revamp of some core components. Why? Because they wanted to make it better.

After 3 years into the project, they realized that was not the way to go. And the main issue that was identified is the fact they didn't try to understand in-depth the reasons behind the initial design solutions to understand the basic problems that it tried to solve. We often see only the tip of the iceberg.

That doesn't mean we shouldn't improve our systems - refactor and improve our code! It just means we better be aware of the history before trying to write the future.

Interestingly enough while traveling into a project's past, you realise what a commit message should be and what it shouldn't be: it should explain why, not what (because I can read the code, I can see that the variable got renamed, I want to know why). And that suddenly makes you realise how terrible you are at writing commit message. You can correct yourself.

It's incredibly useful to tie commits to a ticket. That opens a new dimension to understanding the context.

Finally as a last resort, if no meaningful artifacts are found, check the author and if they are still around ping them and ask why.

This is my code travel guide. I hope you'll find it useful.

Having talked all about git blame, made me think of another story.

Imagine a regular day at the office. Suddenly the reporting tool starts flashing red, everybody is getting notifications on every email, the alarm in the room goes off, there are lots of 500s happening on production. Panic-panic! Team gets together really fast, figures out what the problem is and hotfixes the issue on production. Everything is back to normal.

Now stage 2 begins: who's to blame and who should we punish?

The team figured it was Miloš who made the commit that broke everything. (At this point the room burst into laughter and I am completely clueless why this is funny. Apparently this is an inside joke - Miloš is the first name of Czech Republic president and he is not a very popular figure.) Everybody starts pointing fingers. Miloš is not fired or removed from the project, but the management is giving him the looks. It's cringy. Ivona, his teammate, even said: "I always thought Miloš is sloppy and something like that will happen eventually." Everybody settled with the root cause of the problem - Miloš, and now they can move on.

This tendency for people to place an undue emphasis on internal characteristics of Miloš (as being sloppy or inattentive), rather than the external factors, in explaining the situation is called the attribution effect. We want to find a simple answer to a complex problem.

Did we actually solve the problem? No, we didn't. Because anyone can be Miloš.

Therefore in an alternate universe.

After fixing the bug, the team gets together and has a different post-mortem. They ask questions: "Why did it happen in the first place? How did it slip into production? How can we prevent these kind of problems in the future?". And they try to find solutions: "Maybe we need better tests, or CI, or a different way of doing code reviews."

Don't find fault, find remedy.

This could happen to anyone. We are humans, we make mistakes. That's why we make up rules and build tools to prevent us from making those mistakes.

That said, we should not keep people that are dragging the project down. Sometimes we have to say no to some people. How we decide who and why should be let go is a complicated matter and I believe every company has its own process for that.

Our next story is about passive aggressive interactions.

This is Özlem. She joined a new team. How exciting!

And this is Mărioara. She's been in the team for the past 2 years - proper old-time team player.

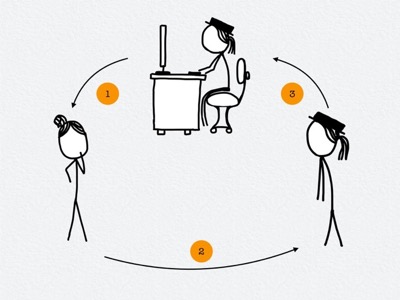

Özlem is excited to get started. She picks up her first ticket, investigates, writes the code, writes the tests - all good. Puts it in code complete.

Mărioara picks it up for a review. She changes some implementation details splitting some functions and rewriting a method. She then proceeds to merge that code and set it as done.

Özlem looks at the changes made, feels a bit awkward to ask questions, so she lets it go. She thinks to herself: "I should probably be more attentive next time."

In a few weeks time Mărioara again picks up one of the Özlem's tickets for review and again moves things around, rewrites variable names, etc. Again no real comments from her. That happens again and again. Özlem remains silent to her growing frustration.

Now let's see the perspectives of both parties involved.

Özlem feels like she isn't even contributing to the project. She can't take ownership of anything on the project, because some bits of her work are being rewritten all the time. She never gets any real feedback on what was wrong and why this different solution is better. She didn't want to speak up, since she was new to the team. Didn't want to be the trouble-maker.

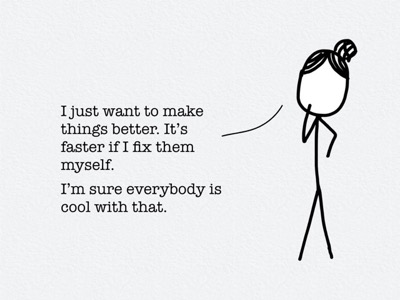

Mărioara does a code review and sees some parts that could be improved, not that the original solution was wrong. She has this itch of just making things perfect. She think it's just faster (hence more beneficial to the project) to fix those things herself, rather than leaving long comments and explaining her vision. She never considered that the author of the ticket is offended or feels alienated.

In an alternate universe.

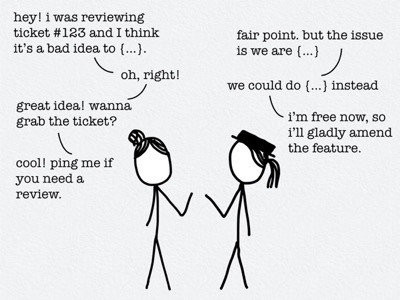

Mărioara reviews the ticket and sees a main point that could be improved. She goes to Özlem and says: "Hey, I was reviewing this ticket and I think it's a bad idea to store that value in the database, since once it expires, it's no use to us. Do you think we might change that and store that value as a class attribute?"

"That's a good point. But the problem here is that we instantiate that class in two other places. So we will have to fetch that value twice, which is expensive.", says Özlem.

"Right."

Özlem goes again: "We could store it in memcache."

"Good idea!", says Mărioara. "Wanna grab the ticket again or do you want me to do it?"

"I'm free now, so I'll gladly amend the feature."

"Nice. Ping me after you're done if you need a review."

Özlem and Mărioara manage to truly collaborate and come up with a better solution than either of them had in mind. Also both feel included. It's so easy to say: "Hey, I have this concern." It's also about offering a choice.

At this point it doesn't matter who will finish the ticket, because they have an agreement and both are looking into the same direction. That way spirit of collaboration and trust can flourish in a team.

Here we are at our final story - the power of we. We as in we together, not the royalty.

This is Haru and Vlad. They work together.

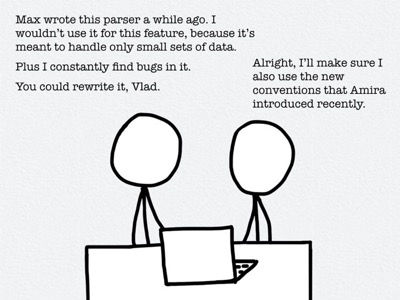

Haru and Vlad are estimating a new feature. On a specific line in the estimate Haru says: "Max wrote this parser a while ago. I wouldn't use it for this feature, because it's meant to handle only very small sets of data. Plus I constantly find bugs in it. You could rewrite it Vlad."

"Alright, I'll make sure I also use the new conventions that Amira introduced recently."

In an alternate universe. You probably see where I'm going with this...

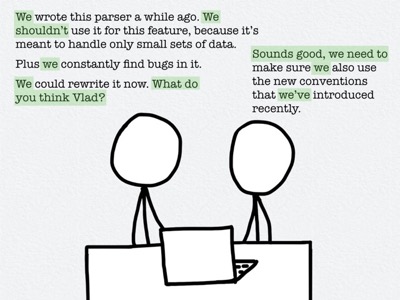

I made an itty-bitty correction. Replace all the pronouns with "we".

"We wrote this parser a while ago. We shouldn't use it for this feature, because it's meant to handle only very small sets of data. Plus we constantly find bugs in it. We could rewrite it now. What do you think Vlad?"

"Sound good, we need to make sure we use the new conventions that we've introduced recently."

"We" gives a strong feeling of togetherness.

This is such a trivial change. But the tone changes straight away. It's a big shift in our heads of how we think about our work and what a team is. We are together in failure and success.

The I vs he/she/they idea extends to communities build around tools, libraries, programming languages. I - part of Python community versus them - from Java/PHP/Go/whatever community. I'd be very glad if we could change the versus to together. And let's not tolerate belittling of others.

I've made all of those mistakes and more. But I believe it's possible to change and I'd like to encourage people around me to change for the better as well.

Influence and changes to the norm of interacting in a team or open source community can be nourished in different ways. One possibility is to have it imposed by a general rule coming from higher up management. But I find that true long-lasting shatterproof rules of interactions come unwritten kicked off by individuals themselves in their everyday social encounters with other people.

Things tend to accumulate and little by little good things and healthy interactions will overflow into something good - like a pleasurable place to work.

All these little stories are just a fraction of what we experience every day on a social level. These stories won't give answers to many situations that we find ourselves in.

That's why you should let empathy and compassion be your guide.

Not only in your professional life, but also when you're driving, getting tomatoes at your local corner shop, visiting family for holidays or ordering pizza.

Thanks! Děkuji! Mulțumesc!